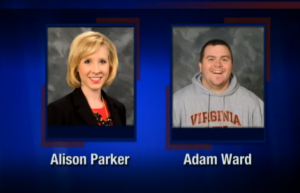

The specter of death lurks in and around the TV news industry every day.

Every reporter and photographer in America can drive around town and point to the spots where they encountered the aftermath of tragedy. Most reporters and photographers also have at least one story of almost “losing it.”

I’ve come close to a mid-air in a helicopter, been shot at a couple of times, been too close to a couple of fires and a chemical spill, and knocked on some doors I probably shouldn’t have. It goes with the territory and I’m glad my proximity to disaster never resulted in harm.

But in reality, TV newsies almost feel immune – they have to. They trust in the idea that for some reason the Grim Reaper doesn’t seem to be able to penetrate their viewfinder or the screen. It provides an arms-length experience that must necessarily come along with dealing with death almost every day.

Sometimes though, Death marches right into the newsroom and delivers a first hand experience.

So today, TV news practitioners are doing a lot of hand-wringing – searching for a “solution” – for a way to somehow reduce the risks inherent in the profession.

But the ugly truth is that there is no satisfying answer to the specter of random death. There is no way to abridge rights based on the suspicion of a person’s future bad acts. There is no way to protect people whose job is to go out into the world every day – into a new and different scenario with endless variables – and somehow assume that none will be killed in so doing.

Live shots after the cops are gone will continue. The competitive push to get the interview with a suspect’s sketchy friends will always be there. The best stories almost always require first going back to the scene. The story, and therefore the job, involves rushing to the war, riot, flood, fire, spill, and sirens.

It always has been that way. It always will be.

And it will never be easy – no matter what it looks like from the newsroom, or your front room.